COVID-19: ‘Fever Hospitals’

May 11, 2020

Tom Jefferson, Carl Heneghan

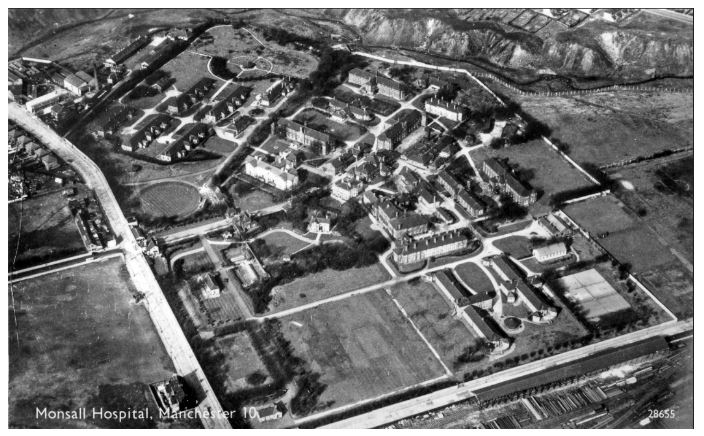

As a child, CH can readily remember the Monsall ‘Fever’ Hospital. You couldn’t miss it, given its vast campus, large stone walls and notoriety with infection.

In 1871 a fever hospital, in Monsall, North Manchester was opened. By 1895 the hospital had 350 beds. In 1948, it joined the NHS and became the Monsall Isolation Hospital. It closed in 1993.

Monsall contained isolation wards, separate accommodation for different infections, laboratory and operating theatres, convalescent wards and activities for recovering patients. In the early twentieth century, four out of every five admitted patients were under the age of 15.

The superintendent of Monsall Hospital, Donald Sage Sutherland, in a 1937 lecture set out the vital aspects of the smaller fever hospitals:

“Regarding the infections of measles and scarlet fever, it is disputable whether isolation at home may not obtain comparable advantages, but for the control and efficient nursing and treatment of the bulk of the common infectious diseases the fever hospital, large or small, still occupies a most important position, and very early removal of cases to hospital should be regarded as the wisest policy both in stamping out the source of infection and in securing the most effective treatment for the individual case.’”

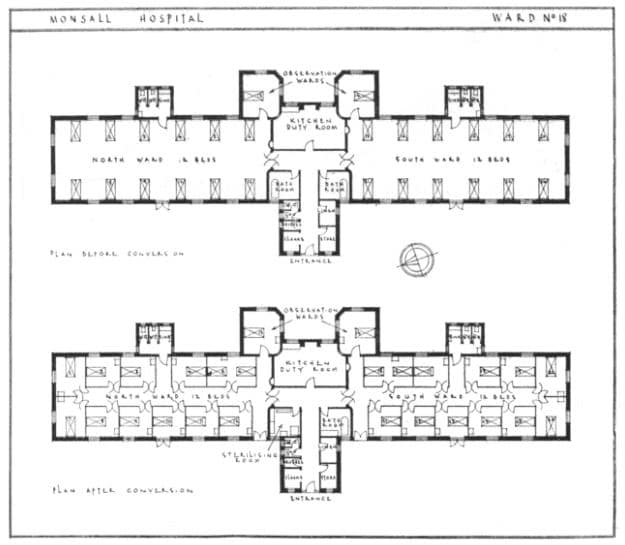

When the need arose, Monsall Hospital converted open-plan wards into separate isolation rooms at a relatively low cost. Each ward was 26 feet wide by 70 feet long and each isolation room had approximately 110 square feet of floor space.

Monsall Hospital before and after plans

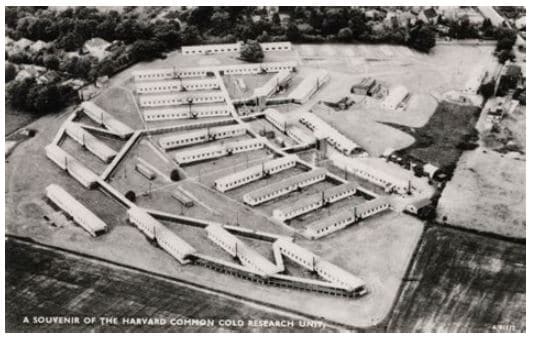

‘Fever hospitals’ were often set in large areas with external walled perimeters to create isolation. This is what a WWII US forces infectious diseases hospital (later the MRC Common Cold Unit) looked like:

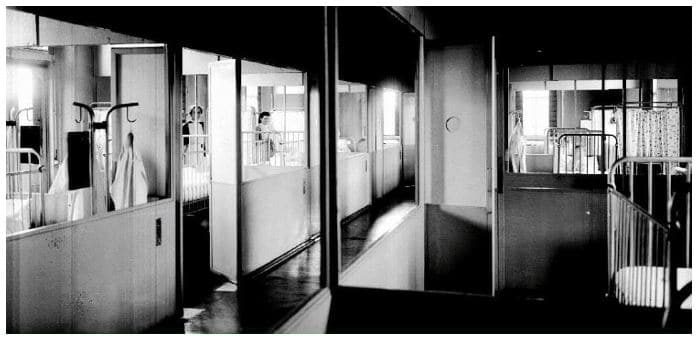

In Monsall the creation of partial walls, glass partitions, and rituals of barrier nursing created a further “isolation within isolation”.

According to Burdett’s hospitals and Charities,1929 Edition, there were 635 fever hospitals of less than 100 beds in England and Wales. Many remained closed except during epidemic outbreaks. Clearly our forebears had grasped the need for a flexible response in times of uncertainty and surge.

The development of immunisations and availability of antibiotics made infectious diseases less common, less serious, and the need for isolation became less of a problem.

Given the current problems with the COVID-19 outbreak, in countries such as the UK and Italy (which have far too few hospital beds – see the table), we need to re-establish ‘fever hospitals’.

Places which are separate from the community and staffed by specialists. Larger community intermediate hospitals could be quickly transformed with isolation in isolation units in an outbreak with critical care capacity that could offer much needed spare capacity. In the non-epidemic downtime, they could be training facilities for infection control and offer intermediate capacity for the elderly who often need rehabilitation and don’t need the high tech care afforded by modern hospitals.

If this solution is not acceptable, the hospitals should be maintained by a skeleton crew, ready for activation in a very short time. If those who read these lines wonder about the expense of mothballing facilities should look up the latest forecasts by HM Treasury and think of the madness of receiving and housing infectious and non-infectious patients in the same facilities.

Legionary hospitals, lazaretts and fever hospitals did not just happen, the lessons were paid for with the lives and sufferings of our fellow human beings.

Table. Hospital and ICU beds by selected European countries.

| Country |

Hospital beds per 1000 |

ICU beds per 1000 |

| Germany |

8.00 |

33.9 |

| Austria |

7.37 |

21.8 |

| France |

5.98 |

11.6 |

| Belgium |

5.76 |

15.9 |

| Switzerland |

4.53 |

11.0 |

| Norway |

3.60 |

8 |

| Italy |

3.18 |

12.5 |

| Spain |

2.97 |

9.7 |

| Ireland |

2.96 |

6.5 |

| Denmark |

2.61 |

6.7 |

| United Kingdom |

2.54 |

6.6 |

| Sweden |

2.22 |

5.8 |

Health at a Glance: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2019_4dd50c09-en

The Variability of Critical Care Bed Numbers in Europe https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22777516/

AUTHORS

Tom Jefferson is an Epidemiologist. Disclosure statement is here

Carl Heneghan is Professor of Evidence-Based Medicine, Director of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine and Director of Studies for the Evidence-Based Health Care Programme. (Full bio and disclosure statement here)